Jakarta | detikperistiwa.co.id

Eighty years ago, this nation was born from wounds, blood, and prayers. Its promise was simple, yet sacred: justice for all. Today, in many corners of the country, that promise feels faint, like an echo slowly fading into silence.

Indonesia is not consistently listed among the world’s poorest countries, as its global ranking varies depending on the indicators used. International economic indices have, at different times, placed Indonesia among lower- and middle-income nations, reflecting the complexity of measuring poverty beyond numbers alone.

Yet statistical portraits often change when confronted with life on the ground. Across vast parts of the country, economic vulnerability is not experienced as data, but as daily reality for millions of families.

Concerns about poverty exist alongside long-standing public anxieties about corruption. International transparency surveys have, in recent years, placed Indonesia in the lower half of global rankings on perceptions of corruption. While some progress has been noted, comparison with neighbouring countries continues to fuel debate at home.

These challenges are deepened by long-standing concerns around bureaucratic governance. Public discussions have highlighted issues such as overlapping institutional authority, procedural complexity, inefficiency, and a governance culture that many observers say remains resistant to meaningful change.

Conflicting regulations have, in practice, turned administrative processes into complicated journeys for ordinary citizens. In many regions, basic permits and services are described by the public as exhausting and uncertain.

Questions about public trust extend further into the realm of law enforcement. Oversight institutions and civil society groups have, over the years, documented large numbers of public complaints regarding maladministration across policing, prosecution services, the courts, and correctional facilities. Common concerns include delays, perceived discrimination, and inconsistency in professionalism.

In public conversation, the legal system is often described through the phrase “sharp for the weak, blunt for the powerful”, reflecting a widely held belief that justice is not always applied equally. This perception, whether fair or not, has had a profound impact on public confidence.

When trust erodes, social tension grows. In some communities, frustration has contributed to instances of vigilantism — not born of strength, but of despair.

Observers and officials alike recognise that the roots of these challenges are complex: issues of professional standards, ethical resilience, legal clarity, political influence, and cultural habits have all been cited in national debate. Efforts at reform have involved improved remuneration, internal oversight, legal restructuring, and public education.

In quiet villages and narrow urban streets, mothers count grains of rice to make them last until tomorrow. Fathers extend their working hours with diminishing returns. Children grow up with dreams that often shrink in the shadow of repeated hunger.

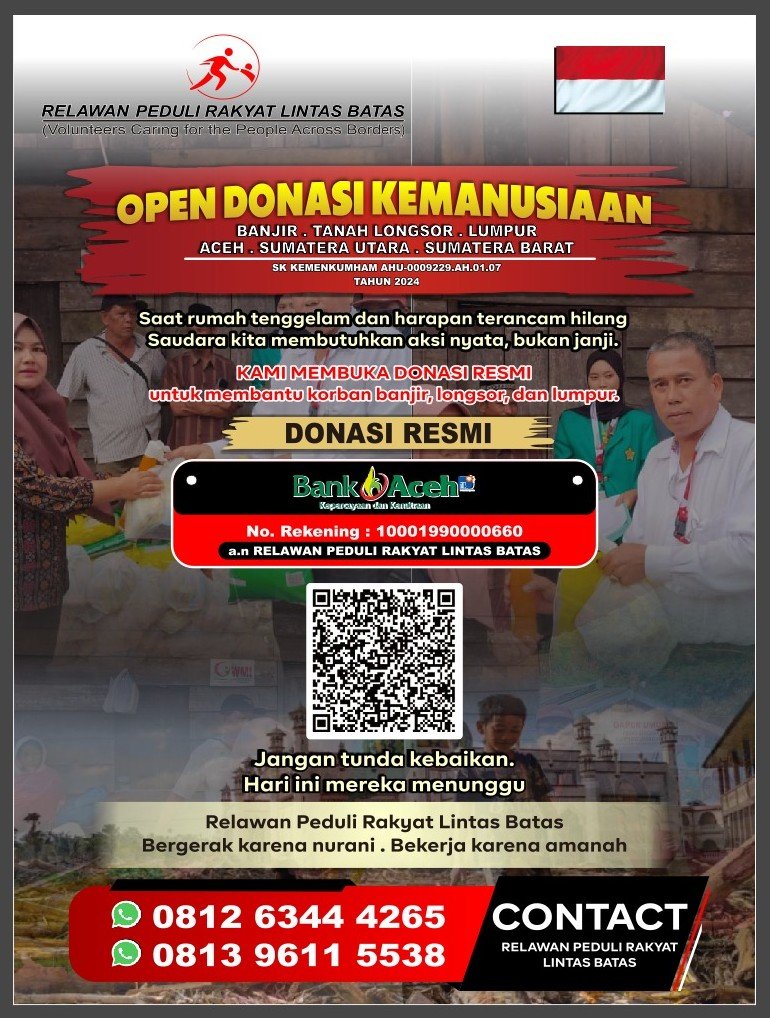

Amid this reality, the Chairman of Relawan Peduli Rakyat Lintas Batas, Arizal Mahdi, has offered a voice that resonates widely among grassroots communities: that Indonesia is not a poor nation, but one that has too long allowed inequality to deepen.

“This country stands upon the tears of its smallest people. Yet those tears are rarely considered in the making of policy,” he said.

He described a reality faced by many families: large numbers of young Indonesians leave their homes and communities to work abroad. They are not seekers of luxury, but ordinary citizens pursuing dignity where hope feels scarce at home.

They send money back, while giving away their youth. They protect their families, often without protection for themselves. They contribute to the national economy, while remaining largely unseen.

“We are not losing workers. We are losing our future in silence,” Arizal Mahdi said.

Eighty years after independence, Indonesia stands at a quiet crossroads: to remain a nation strong in statistics yet fragile in conscience, or to become, once again, a home that feels warm and fair to its own people.

The people do not ask for paradise on earth. They ask only to live without fear. Without hunger. Without being treated as though they are invisible.

Perhaps this is the greatest struggle of the nation today: not against a foreign power, but against forgetting – forgetting that this country was born from the prayers of ordinary people.

(Arizal/red)